For book/ebook authors, publishers, & self-publishers

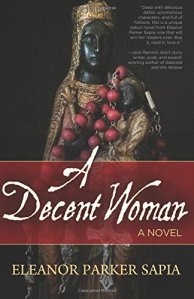

Title: A Decent Woman

Title: A Decent Woman

Author: Eleanor Parker Sapia

Publisher: Booktrope

Genre: Historical

Purchase on Amazon

Ponce, Puerto Rico, at the turn of the century: Ana Belén Opaku, an Afro-Cuban born into slavery, is a proud midwife with a tempestuous past. After testifying at an infanticide trial, Ana is forced to reveal a dark secret from her past, but continues to hide an even more sinister one. Pitted against the parish priest, Padre Vicénte, and young Doctór Héctor Rivera, Ana must battle to preserve her twenty-five year career as the only midwife in La Playa. Serafina is a respectable young widow with two small children, who marries an older, wealthy merchant from a distinguished family. A crime against Serafina during her last pregnancy forever bonds her to Ana in an ill-conceived plan to avoid a scandal and preserve Serafina’s honor. Set against the combustive backdrop of a chauvinistic society, where women are treated as possessions, A Decent Woman is the provocative story of these two women as they battle for their dignity and for love against the pain of betrayal and social change.

Chapter One

La Conservadora de Asuntos de Mujeres ~ The Keeper of Women’s Business

Playa de Ponce, Porto Rico ~ July 1, 1900

On the morning of the Feast of the Most Precious Blood, Serafina’s waters discharged and labor pains commenced. Ana Belén hurried along the dirt road as ominous storm clouds rolled in from the east, threatening to obscure the last of a hazy sunset. The only sound on the deserted street, save for the bleating of a goat in the distance, was the rush of the ocean. When the winds picked up and the first ta-ta-ta sounded off zinc roofs, Ana was nauseated, all part of the familiar heaviness she now experienced before every storm. She lowered her head as the first raindrops dotted the dusty road ahead and noticed cool rain droplets glistening on her ebony skin. Pulling the heavy linen skirt up to her knee to avoid the splatter of mud, Ana picked up her pace. Inside the black leather satchel she gripped tightly, the steel instruments jingled with every step.

Heavier raindrops pelted the dirt street and bounced before settling into the warm, wet earth. That’s the way it always was; the rain formed narrow streams in the parched riverbeds that created fast-flowing creeks. A few days later, the water would find its way back to the sea–the source–or dry up. What a waste of energy, thought Ana. In a few days the streets of La Playa would return to dry, cracked earth. When the wind switched direction, a palm frond flew by, inches from her face, and rain soon followed the wind. The acrid smell of burning sugarcane reached her nose; always a reminder of her childhood in Cuba as a slave.

A black dog with white markings around the eyes barked, startling Ana as she approached the small, white clapboard home of her client. As was her custom before a birth, Ana removed a small knife with a one-inch blade from her pocket. She placed it under the house to keep away evil spirits, and to hopefully cut the length of labor for her client. Ana knocked once on the weathered front door, and stepped back, surprised by Roberto Martínez clutching a squawking chicken by its scrawny neck. He hurried out and then looked back at her. With a quick jerk of his head, he flicked curly, black hair away from his eyes, and motioned for Ana to enter the house. She nearly shouted out to save the chicken carcass for Serafina’s first meal of broth following the birth, but decided against it when a flash of lightning struck over Ponce harbor. Before Ana could ask how his wife, Serafina, was getting on, Roberto had disappeared around the house.

The door creaked open and the familiar aromas of fried garlic and onion welcomed her, confirming the hen’s imminent demise and signaling–in Ana’s opinion–the proper first step in preparing every meal.

She shut the door behind her, and soon her eyes grew accustomed to the dim lighting, which emanated from a solitary lit candle inside a rusty, faded blue tin. Pearls of hot wax from the burning candle settled in a small pile near a wood box of white candles. The one-room house was small and tidy with several cast iron pots on the wood floor for catching rainwater–a common sight in hurricane season. Ana laid her satchel on the floor and lit the wick of the oil lamp. She counted ten candles, and was pleased to see a few newspapers on the table and a stack of folded rags on a chair. Roberto had listened well. When she raised the wick, the silhouettes of a bed, a dresser, and a low table were illumined behind a gauzy curtain. Ana replaced the glass globe on the oil lamp, pulled the curtain aside, and found Serafina sleeping in an iron bed. The image of the two small windows on either side of the bed resembled a cross; Ana prayed it was an omen for a short summer storm and a quick delivery.

Ana removed a hinged, tin case with leather handles from her satchel and took out a blunt hook, steel, scissors, and a crochet hook. One by one, she placed the instruments in a straight line on a white cloth covering the bedside table. The smell of birthing fluids permeated the already stifling house, made more pungent by the closed shutters. Hoping a bit of fresh air might also settle her queasy stomach, Ana pushed open the wooden shutters and fanned herself, thinking the codfish she’d had for lunch might have gone bad. Somewhere in the harbor, a lone foghorn lowed mournfully, filling Ana with a sense of dread. Behind her a voice said, “Are you Doña Ana, the midwife?”

For a moment, the voice sounded far away, and then Ana turned around. “Yes, I’m thecomadrona. I thought you were sleeping.” A contraction tightened around Serafina’s abdomen. The young woman held her belly and rolled her head on the thin pillow, clenching her teeth until the contraction subsided. Several gold bracelets graced Serafina’s thin wrist and a gold crucifix hung from a substantial gold chain around her delicate neck. Ana guessed a merchant marine as wiry and young as Roberto Martínez could make quite a bit of money.

Serafina lifted herself onto her elbows. The light from the candle’s flame was reflected in the gold aretes dangling from the girl’s earlobes. “¿Es un huracán?”

“Nena, nó; it’s not a hurricane,” Ana said, hoping her voice showed no sign of concern. “It’s only a storm, my girl. How often are the pains?”

“I don’t know…maybe every two or three minutes?”

Ana helped Serafina out of her chemise, soiled with birthing fluids, and dressed her in a freshly laundered slip before placing a layer of newspaper under the sheet. “Why did he wait so long to call me? Your husband, I mean.”

Serafina raised her eyebrows and shrugged. “His sister was meant to be our midwife, but my baby is late. She has her own children to care for.” Serafina studied Ana. “Excuse me for staring, Doña. I’ve never seen eyes like yours. They are green and brown in this light.”

“Yes, I’ve heard that before,” Ana replied as she checked Serafina’s cervix. “You are very close to pushing. Do your best to rest between contractions; it won’t be long now.” Serafina closed her eyes, and Ana leaned out over the windowsill, feeling the dampness on her forearms. Through an embroidered handkerchief, she breathed in el sereno, knowing the night air was not good for her or Serafina. White-capped waves, showcased by the lights of the new wharf, rushed toward the shore, and exploded onto the boulders below. Lightning slashed a jagged path across the night sky, illuminating the craggy rocks near the house and the objects inside a paint-chipped cabinet. As if on cue, mismatched glassware and assorted plates tinkled and rattled inside. A tempest was imminent.

Ana remained vigilant at the open window for the egún, the spirits of the dead. The oldbabalowa-the village priest, whose wrinkled and gnarled body resembled the roots of the ancient Ceiba tree, had told the patakí,the sacred story, of evil spirit soldiers hidden in the waves and the wind. The thick, uneven scars on Ana’s shoulder ached as they always did during the rainy season–a somber reminder of him. Her chest tightened as she prayed that the spirit soldiers, who were determined to collect more souls in service of the warrior goddess Oyá, would not come collecting her debt. Ana had never imagined a new path would open for her the moment El Mulato took his last breath. The last time she’d seen him was on a night of rough seas and despair.

“Oyá, ten piedad,” Ana whispered, asking the goddess for mercy. She straightened her back as a lightning bolt cracked over the harbor. Reaching deep into the pocket of her floor-length, linen skirt, she pulled out a rosary, a gift wrought by her mother’s hands—a rosary made of the deadliest of all seeds, the red precatory. During their days of slavery, Ana’s mother had told her the pecatory bead rosary served many functions–for prayer, suicide, and murder, as mashing one tiny bead could kill quickly if ingested. Ana closed her eyes, made the sign of the cross with the silver crucifix at the end of the rosary, and in a low voice, recited prayers the priests had taught her. Every now and then, she opened an eye, watchful for the egún. The spirit soldiers were known to possess great stealth. She breathed in the dust of her ancestors, and felt fear and restlessness in her heart.

Ana invoked the orisha, the goddess Yemayá, mother of the ocean and all creation, to calm her daughter Oyá, the owner of winds and the guardian of the cemetery. Ponce needed the softer side of the goddess that evening. Deep rumblings of thunder echoed through the small house, alternating with lightning strikes. “Ay, Santo Dios,” Ana said, making the sign of the cross again when the rolling thunder caused the floorboards to shudder under her feet. She brought in the shutters, and felt certain from the looks of the menacing, dark clouds and the sweeping winds, that La Playa would not escape a bad storm.

“We’re going to die, aren’t we?” Serafina looked intently at Ana. In the dim light, the girl seemed younger than sixteen. Ana removed her knitted black shawl and draped it over the back of a wooden chair.

“Muchachita, we’ll be fine. Don’t you worry; rest now.” Ana patted the girl’s hand, detectingAgua Florída cologne in the girl’s hair, as long and thick as a horse’s tail. Wide-eyed Serafina bit her lip, and seemed to search the midwife’s face for signs of a lie, or perhaps she smelled Ana’s fear. Ana tried ignoring the thunder and the lightning in the distance, and managed a smile. Couldn’t the goddesses have waited one more day for this baby to be born? The neighbor Ana was mentoring had promised to assist in the delivery that evening, but in light of the weather, she knew the woman would not come.

Ana had considered asking Roberto to move Serafina to the parish church for safety when she’d arrived, but when the skies turned darker, she’d decided against it. The small wooden house didn’t inspire great confidence, but it had survived San Ciriaco. That brought Ana a little comfort. She rested in the hope that young Serafina’s labor and delivery would be quick; besides, the parish church would surely be full of people, offering no privacy for a laboring mother. It was imperative to remain watchful for signs of a hurricane.

When the room grew dim, Ana lit a second candle and set it in the tin. The shadows of the flickering flames danced across the walls, spurred on by a short gust of wind, and then softened by a gentle trade wind. Ana pulled at the sides of her sweat-soaked blouse, shivering against the cool, wet fabric. Her nerves felt as erratic as the flame’s dance. The items she’d asked Roberto for—hot water, clean cloths, and a basin—were in place. Focusing on the task at hand helped calm Ana’s nerves as outside the walls of the humble house, the dance among the wind, the rain, and the ocean began. The fierce winds shifted course, and rain found its way inside the house through cracks in the walls and between the slats of the shutters. Somewhere, the sound of shutters slamming against a house caused Ana to wince. She looked back and Serafina sat up, startled. “Don’t worry; it’s only the wind.”

Ana tugged on a knotted strip of purple fabric someone had tied to the iron headboard for spiritual protection, and she was pleased. Oyá’s color–someone had given the girl good advice. Knowing she couldn’t run from the egún or her responsibilities to Serafina and the baby, Ana tucked a stray, wiry ringlet under her white cotton tignon, and waited for the next contraction, which came quickly. Ana touched her mouth when she tasted blood. She wiped her bloody fingers on her skirt as a dull ache throbbed at her temples. The metallic taste of blood reminded her of him, but this was no time to think of him. She pushed her fear deep inside, and cut her eyes toward the window, thinking of the celebratory cigar she enjoyed after every birth. The thought offered a sliver of hope the birth would go well, but Ana couldn’t shake a sense of foreboding.

Ana mopped the sides of her face with the hem of her skirt as she peered between the slats of the shutters. Cold beads of sweat ran down her back. “Qué loco,” she whispered when she caught sight of Roberto. She touched the beaded necklace around her neck, remembering how cocky and sure of himself he’d appeared when he told Ana he would return to sea soon after the birth. Ana had replied it depended on Serafina and the baby, but now she sensed Roberto would do as he pleased. The young man challenging the wind and rain was headstrong and stubborn.

Recently turned sixteen, Serafina was a pretty girl with hair the color ofcafé colao, eyes like pale green sea glass, and a small mole on the right corner of her full lips that broke the prettiness of her oval face. Serafina, with her perfumed hair and gold bracelets, reminded Ana of the goddess Oshún, the orisha of love. Had this pale, delicate girl with the coffee-colored hair wanted a pregnancy so early in her brief marriage? Ana shook her head, mystified at how many women of La Playa didn’t practice birth control. Had this young couple made any attempt to prevent a pregnancy? More than likely, young Roberto Martínez refused contraception. And now here they were.

Serafina moaned and squeezed her eyes shut during the next contraction. She held her belly with shaky hands. “I don’t think I can do this,” Serafina shouted, struggling to sit up.

“Cálmate, cálmate, these are good contractions. Don’t hold your breath. Let’s see where we are.” Ana placed two chairs about two feet apart, facing the side of the bed. “Sit near the edge of the bed and lie back,” she instructed, helping Serafina maneuver into position. ”When you feel the urge to push, I will help you.” Ana wiped the sweat from her forehead with a sturdy forearm. In the area between the chairs, she positioned a large cloth and placed a basin on it, just below Serafina’s bottom. She set a wooden stool between the chairs, just above the basin, and asked, “Are you ready, child?” Serafina shrugged.

With a gentle hand, Ana pushed Serafina’s stiff shoulders back onto the mattress, and pulled the girl forward. She washed her hands, spread lard on Serafina’s inner thighs and labia, and introduced her hand under the slip. She opened the labia, and passed her fingers into the vagina. Serafina winced. The cervix was soft and fully dilated. Ana hoped the baby would pass through the birth canal without incident, and wondered if the young mother was mentally prepared to deliver a child. At this age, they hardly ever were. “It won’t be long now,” Ana said, seeing the bloody show on her fingers. The pinging sound of water dripping into the aluminum pots echoed from the main room.

“I hope this pain doesn’t get any worse! I have to push!” Birthing was difficult for all women, and young girls needed extra coaxing and mothering. Ana prayed the ill-timed storm would not complicate her already delicate task, but whether or not they were ready for the birth was inconsequential; the storm was upon them, and Serafina’s body was ready. The girl sat up, grabbing at the sheet, and cried, “I’m scared! It is a hurricane! I want my mother!”

There it was. The conversation Roberto had urged Ana to avoid–Serafina’s mother’s death. There was nothing Ana could do to ease the girl’s suffering about losing her mother in Hurricane San Ciriaco, but it was critical to distract her now. Ana twirled a mass of Serafina’s thick curls, willing the hair to remain in place, and took Serafina’s face in her hands. “Listen to me, nena. You can do this. Your mami is with you; she will always be with you. But right now, you’re going to push this baby out, and while I’m here, nothing will happen to you or your baby. Do you understand?”

Serafina nodded, but didn’t seem comforted by Ana’s words. It was crucial to bolster the girl’s confidence before she did something like pass out from the pain. Serafina’s petite body shuddered under Ana’s hands as she began pushing.

Ana glanced over at the low table, making sure the scissors were where she could reach them. Outside, something substantial hit against the wall. The women gasped, jerking their attention to the side of the house. Ana moved deliberately around the cot, feigning confidence that was more difficult to muster now that the storm was upon them. She’d vowed to remain calm if the storm got any worse, and at the moment was finding it difficult to keep that promise. Serafina covered her eyes with her wrist, and tears streamed down her pale cheeks. Ana moistened Serafina’s parched lips with a cool rag, hoping the delicate girl held energy in reserve for the decisive moments ahead. The Martínez baby was two weeks late, and Serafina’s waters had already broken; there was now the worry of infection. Ana would have to employ all her skills to ensure a speedy delivery.

The flames of the white candles flickered rapidly, illuminating the garishly painted faces of two small plaster statues—La Virgen de Guadalupe, the patron saint of Ponce, and La Virgen de la Candelaria, the patron saint of the Canary Islands, where she’d heard Serafina’s people were from. A current of cool air found its way into the house, offering a brief reprieve from the heat, and with it a new threat–total darkness. “Virgencita, don’t let the candles go out!” Ana said, forgetting her vow to remain calm. While there was still light, she checked Serafina’s cervix with the sound of waves pounding the rocks, and the whistling wind sneaking through cracks in the walls all around her. Ana wondered where Roberto was. “As if we don’t have enough to worry about,” she muttered. “Roberto!” Her voice sounded less controlled and higher-pitched than she’d intended. Maldito hombre, where could he be? She couldn’t worry about him as well, but deep down she knew she’d need him in case the storm turned into a hurricane. The driving rain, beating on the roof like dundun and batàdrums, reminded Ana of her childhood, and made it impossible to hear.

When the next violent pain wracked Serafina’s body, she took a seething inhalation before pushing. “I see your baby’s head!” Ana’s skin tingled with anticipation as it did with every birth. She snatched a clean, white cloth from the bedside table, and dipped two fingers into the can of lard. Ana massaged and coaxed the perineum with her index finger until the baby’s shiny, wet head crowned and was delivered. “Pant, Serafina. Stop pushing for a moment!” A sense of urgency and excitement came through when Ana saw the thin membrane covering the baby’s head and face. Ana gasped softly and whispered, “Oke.” It was a caul. A translucent membrane covering the baby’s head and face; a valuable good luck charm for sea captains and sailors, who believed the caul, would protect them from death by drowning. Ana had never delivered a caulbearer before, and as she struggled to remember what she should do next, Serafina pushed one last time. Ana delivered the shoulders, allowing the baby’s body to slip out into her experienced hands.

Ana lay the infant gently on the bed, and with the utmost care, she peeled the thin membrane off the baby’s face and head, careful not to tug on delicate skin. As Ana dropped the caul in the bowl on the floor, the baby cried. Serafina made the sign of the cross and lay back, shaking from exhaustion. The smell of blood and birthing fluid permeated the small room, adding to Ana’s queasy stomach. She would tell Serafina about the gifts the gods had bestowed on her daughter later, when the time was right.

“I see you, little one,” Ana murmured, clamping and cutting the cord. She swaddled the infant in a warm blanket. “She’s a beautiful baby, Serafina. What’s her name?”

“Lorena,” Serafina breathed before retching over the side of the bed.

Ana kissed the baby’s forehead. “You’ve made quite an entrance, Lorena Martínez. I will bury your placenta, and plant a fruit tree in that place, so you will know where you were born, and never go hungry. I will keep your caul safe, and now that I’ve said your name, no one can ever change yourorí, your destiny. Like me, you are the firstborn, and your destiny name is Akanni. Welcome to the world of suffering, my girl.”

***

Ana puffed twice on the cigar and threw back a shot of rum. She closed her eyes, enjoying the burn at the back of her throat, and the familiar tingling in her knees, signaling her body was beginning to uncoil. She lowered her jaw to relieve the pressure in her eardrums. Although mother and child were sleeping soundly and Ana was filled with renewed hope, she also understood no one could fully relax–even now, the storm could produce a hurricane. She tore a page out of her ledger, and delicately placed the caul flat on the paper, careful not to stretch it too tautly. She folded the paper in half and finished by tying a string around the small parcel. Did the young couple know about caulbearers, and the exorbitant prices the cauls went for in the seafaring world? Roberto was a sailor, of course he knew, she thought.

Ana put the wrapped caul in the pocket of her skirt, and felt the otánes in the other pocket, recalling her mother’s tear-stained face as she’d placed the three blessed pebbles in Ana’s hand. They’d hugged tightly until her father pulled them apart, and shoved Ana into the bowels of the ship. Ana’s body shuddered at the memory of the ship’s crossing from Cuba to Porto Rico in the middle of the night.

Moments later, Ana’s attention turned to the violent, unrelenting winds that shook the Martínez house, and flying debris banging against the corrugated zinc roof, inflicting mortal terror in her heart. In the parish church, Ana knew the faithful would plead with the Blessed Virgin to spare them, their loved ones, and their homes; the homeless and those who thought themselves less worthy of salvation sought refuge in the same parish church. Saints, sinners, and doubters sat side-by-side, each casting judgment toward their fellow brothers and sisters.

A familiar howling sounded through the cracks and holes in the wooden walls. When the roof lifted and banged down, Ana looked up and froze. Seconds later, Roberto stood in the house. Serafina brought the mewing newborn closer to her chest. There was no need to speak; they knew what was coming. Roberto pushed the bed into the corner away from the window, and helped the terrified women under the bed. As if hoping his weight would keep the bed from lifting if the roof blew off, he lay face down upon it and covered his head. When the shutters burst open, the women screamed, turning their heads toward each other. Ana didn’t know which ear-piercing scream had been her own, and imagined a huge wave would soon engulf and swallow the house. The zinc roof twisted, groaned, and then ripped clean away from the walls, disappearing into the black sky. Ana prayed Roberto was heavy enough to keep the bed in place as she and Serafina huddled together, protecting the baby between them.

Ana’s muscles cramped, and she would not remember how long they waited in the same positions. What she would remember, opening her eyes for the briefest of moments, was watching the two statues of the Virgin Mary crash onto the slick, wet floor boards and the taste of salt water in her mouth. Small, wet shards of glistening bright blue, white, and yellow littered the floor amidst wet sand and dirt. Ana prayed fervently until the storm veered northeast, and the rain stopped.

Views: 77

Comment

© 2024 Created by John Kremer.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of The Book Marketing Network to add comments!

Join The Book Marketing Network